The Science of Pain

From the sting of a paper cut to the excruciating ache of a broken bone, pain is the body’s way of telling the brain that something is wrong and needs attention. In this way, pain is the body’s way of protecting us.

Despite the fact that pain is a part of everyone’s life, scientists know surprisingly little about how it works, and how drugs help quell pain.

What has been known for centuries is that the body is wired with nerves that extend to everything from our internal organs to the very superficial layers of skin. These nerve receptors detect changes in our environment – like fluctuations in temperature, vibrations and, of course, pain.

The information collected from these receptors is sent to the central nervous system, which includes the brain and spinal cord. It’s the central nervous system that processes and interprets all of these messages.

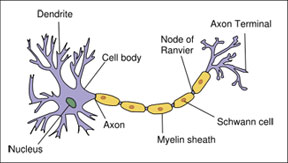

For example, when you cut your hand, the pain receptors, or nociceptors, within the skin on your finger detect the cut and send the information to your central nervous system. These messages are coordinated through a series of nerve cells that communicate with each other. Nerve cells contain dendrites, which are processes, or extensions, that can be thought of as the cell’s “fingers.” When dendrites detect a stimulus (like the signal coming from a paper cut), the signal is sent through the length of the cell, and along it’s axons.

Each cell can relay information or “talk” to other cells next to it. By relaying information from cells to cells, eventually the signal reaches the central nervous system. When these signals reach your brain, you consciously perceive the sensation of pain from your paper cut.

For serious pain, doctors might prescribe medication, like morphine, to block the feeling of pain.

It’s not clear exactly how morphine, a well-known opioid, works. However, scientists do know that morphine binds to receptors that are located in the central nervous system that are involved in modulating pain.

Over time and with increased dosages, morphine can lose effectiveness. It’s not fully understood exactly why or how this tolerance occurs.

Even more confounding is pain that doesn’t seem to be stimulated by a specific irritant. Many amputees, for instance, describe feeling pain from missing limbs – this is known as phantom limb pain. Also, some people suffer from neuropathic pain, which is caused by problems or disorders with the nervous system.

In these cases, figuring out how to manage pain is difficult. Persistent pain is a medical problem that has yet to be solved.