China’s Generation Green: Reporters’ Notebooks

This month fellows of the UBC School of Journalism International Reporting Program are traveling throughout China, profiling young Chinese who are trying to make a difference in their country’s environmental future. Below are daily notebooks from reporters in the field.

Beijing, December 16 2013

Carlos Tello

A couple of days ago, Allison, Angel and I went to Tiananmen Square at sunrise to shoot video during the flag-raising ceremony. We managed to record the flag as it was going up, and also the hundreds (if not thousands) of tourists gathered at the square to watch the ceremony. Everything went well for the first half an hour, but, while shooting the Monument to the People’s Heroes after the ceremony, several security members approached us to inquire about our filming.

When they reached us, I feared for the worst. After all, we were at Tiananmen Square — mostly known around the world for the violent repression of protesters in 1989. But the security members calmly exchanged some words with Angel, peeked a couple of times on the display of the video camera and told us that we had to get a special permit if we wanted to record in the square. They did not ask for our materials or even ask to watch our video.

Our encounter with guards at Tiananmen Square reminded me of how much our preconceptions can influence our understanding of the complexity of China. This country with its rainbow of political, economical and social actors — and its environmental issues are so far some of the most complex topics I’ve ever had to report on.

Kunming, December 15 2013

Peter Klein

My last airport dispatch. In a country of 1.3 billion people, what are the chances of bumping into people you know at the airport? On my flight to Hong Kong are two tourists we interviewed the other day, hundreds of kilometres from here, up in the mountains where the snub nosed monkeys live. They are en route home to Hong Kong.

Incredible that people make the long trek to see these monkeys. Raising awareness of this charismatic species has led to habit protection in other parts of the world, and it seems to be happening in China too. The mountain forests where these snub nosed monkeys live have been a reserve for years, but only since attention has been focused on the creatures have the logging rules begun to be enforced.

Shangri-La, December 15 2013

Peter Klein

In my continuing effort to serve as airport signage correspondent for the “China’s Generation Green” project, below is a large ad prominently displayed at the Shangri-La airport, urging people not to eat shark fin soup. This popular Chinese delicacy has been tied to several species of shark becoming threatened or endangered, and a movement led by hip young people is trying to stigmatize the consumption of soup made from shark fin. A similar protest movement exists in Vancouver – I have seen protesters in front of a popular Chinese restaurant on Main Street urging the restaurant to take shark fin soup off its menu.

Chengdu, December 11 2013

Aurora Tejeida

Our food safety team recently returned to Chengdu, after spending a few days at Anlong Village, an ecological farm about 40 km west of the city.

During our visit we interviewed Ming Jai-Li, who works for CURA (Chengdu Urban River Association), an NGO that is helping the farmers. Jai-Li told us China is importing more food, and farmland is quickly disappearing. That begs the question: how will China feed its people in the future?

While China accounts for one fifth of the world’s population it only occupies nine per cent of the land and an even smaller percentage of arable land. According to China Daily, arable land in China went from 130 million hectares in 1996 to 121 million hectares in 2008.

The current per capita cultivated farmland is only 40 per cent of the global average. While we were at Anlong, we learned that the government has plans to turn the village into an ecotourism spot, building artificial hot springs on farmland.

The efforts to farm ecologically at Anlong are both a response to the demand for healthy/pesticide free vegetables and a way of decreasing the amount of pollution pumped into a nearby river. But the NGO has had little success in replicating the village model and getting more farmers to join the cause. The fact that the government is pushing rural populations into its cities only adds pressure on the land in China and overseas.

According to Reuters, China plans to buy 3 million hectares (7.4 million acres) of Ukrainian farmland. That would make Ukraine China’s largest overseas farming centre.

All of that begs the question: What is the future of a village like Anlong? It is so far unclear when the government will act on its plan to create an eco-resort. As one of our interviewees said, China is changing so fast that it’s a different country every five years. No one knows where the next China will have a place for villages like Anlong.

Chengdu, December 11 2013

Katelyn Verstraten

Here is the Chengdu sun, as of eight this morning. The hazy smog is still surreal to me. The first thing I’m going to do when I’m back in Vancouver is take a deep breath of salty air! It makes reporting challenging because your first thought is not always “am I getting everything I need” but “should I be wearing my smog mask?”

Beijing, December 11 2013

Emma Smith + Britney Dennison

Today we visited the International School of Beijing. This school has been attracting a lot of media attention this year. Last week CCTV, Chinese state television, dropped by. They have also been interviewed by CBS News and MSN News. The reason – a one-million dollar pollution dome. The dome is the most dramatic example of how people in Beijing are coping with air pollution.

When you pull up to the school the domes (there are two of them) loom in the background. Entering a dome is like walking into an air capsule; it’s pressurized with air locks so that pollution can’t seep in. As you spin the revolving door, your ears pop as they adjust to the change in air pressure. When the air pollution (PM 2.5 – a fine particulate matter) levels reach above 150 kids do exercise and recreational activities in the dome. This is the most extreme step any school in Beijing has implemented to keep kids safe when air pollution is high.

We knew we wanted to see “the dome” in Beijing. Who has ever heard of kids having a playground with a lid on it? It sounds like sci-fi novel. But here it makes sense. We’ve been outside on days when you could see particles in the air. You really feel as though you shouldn’t breath.

Beijing International School is the one-percent exception to most schools here. You can’t get in unless you and your parents have foreign passports. Tuition is about as much as an ivy league school in the U.S.

For most school kids in Beijing, when the air quality is bad they remain indoors and work at their desks. Most schools keep children inside when the particle count is 200 PM – four times more than the WHO recommends.

Last week we met a family whose son has been sick from the air pollution. Their only strategy to keep him safe is to have him remain indoors. Neither his home, nor his school have air filters. We would have liked to have visited his school, to see the difference for ourselves. But on a tight timeline with so much to see we’ve had to make tough choices.

Dali City, December 10 2013

Umbreen Butt

We had to interview our most important subject today: China’s top nature photographer. Learning from our mistakes in Beijing, I had asked my partner to request our interviewee to warn us an hour before he arrived so I could set up. He was late, but it gave me time to ensure that my setup was immaculate. We were prepared.

This time, I had requested my partner to translate all of the questions from English to Mandarin before we started. That way, she would not have to translate on the spot, which put immense pressure on her. So I would ask the question in English, she would read the translation in a conversational tone, and our interview subject would proceed to respond: a much smoother process.

In our previous interview, my partner would translate the answers almost word for word: a process that became increasingly lengthy as her sugar level dropped. This time I requested summaries instead and we kept chocolate and tea close at hand.

But no interview is without its hiccups. I read my partner’s nervousness as pressure due to our interviewee being in a hurry. So, as soon as he came in, I sat him down, turned on the lights, pinned on his microphone and began.

He stopped us, immensely annoyed. He was not prepared for a video interview. As his staff did not give us his phone number until the day before, we actually had no idea how much he knew and what his expectations were. This could have been prevented had I taken a few minutes to introduce our project rather than to jump right in.

Our interviewee objected that nature photographers should be interviewed outdoors rather than indoors. In fact, he insisted that we do so. I did not want to acquiesce, but I thought that I should at least appear willing.

Outside the sunlight was hard and would create stark shadows on his face. The traffic noise would not give us a clean track of audio. I knew that his interview would potentially run under the footage of other nature photographers working in the field. And so, in spite of his objections, in spite of his seniority, in spite of his chagrin, I insisted that we conduct the interview indoors: softly, yet firmly.

Especially, I insisted, as we had taken such pains to make him look so darned good. And I smiled at him, and winked at my partner and shook her playfully, which broke the tension, even if just momentarily.

Anlong Village, December 10 2013

Jimmy Thomson

We spent the last three days based in Anlong Village, a small farming community of about 30 families. Given the proximity to the metropolis of Chengdu, it was not surprising to find evidence of one of the dominant trends in China – the largest movement of people in history – playing out there.

Next to the village is a new housing development, purposely built to encourage farmers to leave their land like so much of the population has done so far. We met with an old woman who has recently moved in, and says she has not been fairly compensated for her land by the government. She showed us a public bulletin of how much money each family owes for their new homes and how much government subsidy is owed to them. The numbers almost match but she says she hasn’t received any of the government compensation

Likewise, our elderly hosts, Grandpa Luo and Grandma Ho, say they would rather keep their farmhouse and their garden. Nonetheless they plan to move into the new housing, fearful that the government could threaten their government-employed children.

Meanwhile, three cranes loomed on the horizon, and below them, the encroaching sprawl of the city. The farmers still work their land but in fewer numbers. Young people working the fields are rare, and those who move into the new condos tend to find jobs in the city, returning only every few days to get some fresh air. A local teahouse does quite well, supplying city dwellers with organic food, natural surroundings, and a dip in the river before the water reaches Chengdu.

Our time in Anlong gave us the perspective we needed to understand what’s going on across China. Urban populations have doubled since 1990, and a further 300 million people are expected to move into cities before 2025.

For Anlong Village that trend probably means more housing developments, more cranes and more pressure to get out of the fields.

Sichuan Province, December 10 2013

Katelyn Verstraten

Delivery day starts early in Sichuan province. Yesterday, I followed a farmer for 13 hours. We started our day at 2:50 am by climbing in to the back of a van packed with vegetables. Cherry, our student partner from Shantou University, sat next to farmer Wang in the front seat. Cherry is originally from Sichuan province. She speaks both Mandarin and the local dialect of Sichuanese. As we bumped along the pitch-black roads, the three of us tried to converse.

After about five hours crunched up in the back of the van, Cherry and I fell into a routine. I would take the photos and ask questions. She would then translate and record, giving me a summary of the answers. It seemed to work, but it makes the job of asking follow-up questions difficult. You are never sure exactly what is being said. It is an exercise in trust. I found making eye contact reassuring. Farmer Wang and I seemed to find away to understand each other.

After our thirteen hour day, we returned to the farm with photographs, audio recordings and five recorded interviews with customers (Cherry commented that we delivered produce that day for as long as it took me to fly from Vancouver to China).

Kunming, December 9 2013

Peter Klein

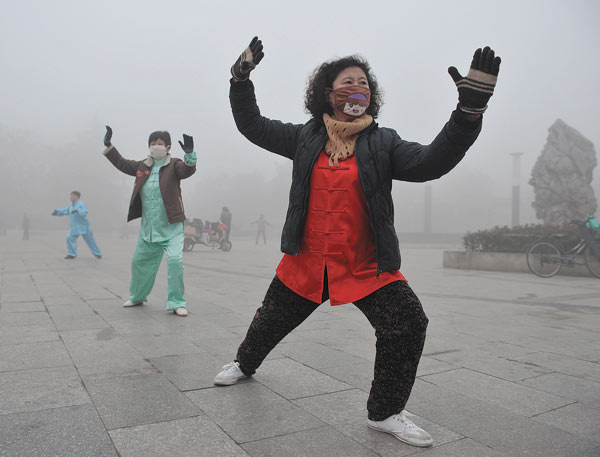

The airport in Kunming boasts the treasures of the Yunnan Province, the lushest of the provinces in China. You can see from these ads how this province has positioned itself as the antidote to smoggy cities in much of the country, a place for “lung cleaning.”

The cover story in today’s China Daily is about the high levels of smog in major urban centres, with an above-the-fold photo of women doing morning exercises in masks amid the smog. Caption: “Nearly half of the country is choked in some of the worst air this year.” So Yunnan is well-positioned to attract those who can afford to get away and breathe a breath of fresh air.

En route now to Shangri-La, a part of Yunnan that was renamed in 2001 after James Hilton’s fictional paradise. There’s controversy over what part of the world inspired Hilton’s 1933 book Lost Horizon, but Yunnan is one of the contenders (along with the Hunza Valley in Pakistan, near the Chinese border). I haven’t looked into whether people in this new “Shangri-La” live forever or not, but if they do, we’ll be on to a really good story.

Beijing, December 9 2013

Umbreen Butt

Driving to the airport on a hazy morning, we spoke with our cab driver about Beijing’s smog.

The night before, we had spent over an hour in traffic traveling from Ring Road 4 to Ring Road 3. Back at our hotel, we heard on the news that flights were being grounded due to the thick layer of air particles that hung above the city. The smog not only presented a health hazard, I reflected as my partner washed her face mask, but had an economical impact as well.

At 6 a.m., the traffic was thin. Our cabbie told us that ten years ago, the number of vehicles on the road was much less.

Ten years ago, I thought, the country’s automotive industry was not churning out as many cars for the local market. How much did the automotive industry targeting domestic users contribute to GDP, that it was allowed to grow in spite of the inability of urban planning to accommodate so many vehicles? Was the industry encouraged through targeted incentives, or was it simply responding to a growing market demand? Could it have been curbed with some foresight on behalf of the government, or was China’s overall policy objective to develop first and fix it later?

And, as a car-user myself, did I have the right to critique an issue which, to me, was more of a hindrance to travel plans, rather than an obstacle to daily life?

Ten years ago, our cabbie continues, the problem was not the smog, but the sand that blew in from the Gobi desert. For an entire day or even two, life in Beijing could be at a stand-still when the dust storms became intense.

I smiled at him: how can intangibles like quality of life be measured, I wondered. Moreover, the reason we report, ultimately, is to understand how the ethical, economic, legal or policy implications of an issue, like air pollution, ultimately affected the everyday lives of ordinary men like our companion behind the steering wheel.

Beijing, December 8 2013

Umbreen Butt

I am glad we did not interview our most important character first. It was a matter of logistics rather than deliberate design, however it worked in our favour.

The learning curve for our first interview was steep. After initial introductions, I should have told my Mandarin speaking partner to engage with our subject while I set up the lights and camera for the interview. In fact, I wished I had instructed her to pick up tea and biscuits from the confectionary stand outside the office to make for a more amiable wait.

However, I sat through the lengthy initial formalities with a smile on my face, unable to understand a word being exchanged, wondering when the process would end. I then set up the lights and camera alone (my partner being non-technical), which took another 45 minutes. I could sense our interviewee’s restlessness.

And with such a rushed setup, I was fidgety when we started: not fully satisfied with the backlight, with the reflection of the key light in our interviewee’s glasses, with my limited ability to move the light as he was wearing a hat.

And so, my concentration on the content of the interview was diluted with my obsession over the details of appearance. I stopped the interview twice to adjust the light.

Luckily, our subject (a photographer himself) had been interviewed countless times and appreciated the attention to detail. The process took four hours…two hours too long in my opinion.

Beijing, December 7 2013

Umbreen Butt

“Hit the ground running” is a statement that applies to paratroopers, not video-journalists. I had underestimated my exhaustion when I arrived in Beijing from Vancouver on a Friday evening.

Our first shoot was scheduled for the Beijing Zoo early Saturday morning. The authorities at the gate were daunting in faux-fur Russian hats and long black trench coats, so I chose not to shoot at the entrance.

My Shantou partner, who was new to this kind of journalistic work, was equally uneasy. She advised me that filming outside of the small zoo office where we had kept our equipment was a no go.

I insisted on pretending I was just taking photographs, and set out with my camera, but without my tripod and lenses.

When I finally arrived I realized that everyone was armed with cameras and super long lenses, some with tripods even. I could have brought my own gear without a problem. But time was short; we had half an hour to take footage before our first interview began.

In hindsight, I realize one needs an extra day in a new country to settle into the local norms and expectations. I had been expecting a tightly managed totalitarian country. Instead, I was confronted with the uncontrolled chaos of Asia.

So, had I simply scheduled shooting at the zoo, I would have made all of the footage that I wanted with various lenses and a tripod. This would have been a no pressure shoot, on a day when I was still tired from traveling, and it would have instilled the confidence in me that I could carry on working alone in a foreign country.

A day upon arrival in the destination country is required in order to decompress from the preceding days, often spent planning insidiously. This time I paid the price by missing an establishing shot of the Beijing Zoo.

Beijing, December 6 2013

Mike Wallberg

Today was our first interview of the trip, which meant we had to be prepared. Time to look like a journalist. The early morning was spent re-learning the audio equipment and discussing interviewing strategy, then it was off to “798”, an artist colony within the city to meet our guy.

We were apparently too convincing, as our interviewee was a little spooked when he met us. Echo was a real pro, though, and made him comfortable. The interview went pretty well, and afterward we strolled the galleries with the interviewee, shooting pics and video and recording audio (we left his wireless mic in place).

Here’s a cool shot Leif took of Peter Herford and me during the walkabout.

No discussion of China is complete without talking about the food. We’ve been gorging ourselves on the local fare since we landed, including a nice lunch after shooting was done. Here’s Echo with our guy, enjoying traditional Beijing noodles.

We head south tomorrow to spend time in the villages. Looking forward to the next challenges.

Shanghai, December 6 2013

Aurora Tejeida

Yesterday was our second day in Shanghai, we shot an activist giving a talk at a private school about healthy eating habits. It was very interesting to be in a bilingual elementary school in China, all the kids spoke perfect English and they were very well behaved. After the activist gave them a lesson about the amount of sugar in common drinks that included several types of pop and juice, the kids had to make citrus flavoured water with blenders.

In any school I’ve studied this would result in chaos, but the kids cut their own limes and lemons, blended their water and played with the sugar without making much of a mess. Most of the teaching staff seemed to be foreign and the school was covered in signs that read “Please only speak mandarin or English.” We guessed that this was meant to dissuade children from speaking Shanghainese, a local dialect that is spoken here.

Overall, it was an interesting experience to be a part of.

Shanghai, December 6 2013

Jimmy Thomson

After a few months of correspondence with Wu Heng, it was great to finally meet one of our main interview subjects. He looks even younger than his 28 years, and just returned from a 5,000 km bike ride from Berlin to Lisbon. He showed us a book he’s been working on, a weighty volume bound in plain blue paper, and passed it around to show the detailed revisions he’s been working on since completing the manuscript. It turns out that chronicling the food safety of a country wracked by food scandals is a pretty serious task.

After a few months of correspondence with Wu Heng, it was great to finally meet one of our main interview subjects. He looks even younger than his 28 years, and just returned from a 5,000 km bike ride from Berlin to Lisbon. He showed us a book he’s been working on, a weighty volume bound in plain blue paper, and passed it around to show the detailed revisions he’s been working on since completing the manuscript. It turns out that chronicling the food safety of a country wracked by food scandals is a pretty serious task.

We did a great interview in our apartment then headed out with Wu to see a nearby market. While he pointed out some of the foods that have been involved in scandals, a rat scurried past. Luckily, Katelyn was aware enough to be both recording his reaction and to not say anything herself, resulting in a great bit of sound that will hopefully have a place in the final piece. There was no shortage of good photo subjects either, from recently decapitated fish still wriggling on their bloody cutting boards to long colourful rows of fresh vegetables.

Next, Wu took us to a restaurant across the street from our apartment. For someone who has spent the last two years as the most prominent food safety watchdog, he was remarkably casual in his own dining habits. He says he eats out about two meals per day – and since organic food costs about ten times as much as regular food, he doesn’t bother with organic either.

Shanghai, December 6 2013

Katelyn Verstraten

How to wear a smog mask in Shanghai:

Step 1: Select your mask. Do you prefer checkers, pink-laced, gas-mask style or sterile white? The choice is yours.

Step 2: Put on mask. Make sure the elastic digs into the bag of your ears properly. If you’re not uncomfortable, you aren’t wearing it right.

Step 3: Step outside. Don’t be alarmed if you can’t see the sky. Your paper or cloth mask will protect you. Hopefully.

Step 4: Always remember you are wearing the mask. Don’t try to eat will wearing the mask. Don’t be alarmed when you see your reflection in the mirror.

Step 5: After removing the mask, apply moisturizer to chafed face. Blow nose – dirt is normal. Remember – the air quality measure won’t always be off the chart. One day you will see the sky again.

Bejing, December 5 2013

Allison Griner

Carlos and I took the day to sleep off our jet lag and prepare for tomorrow’s interviews. There was the panic of unpacking and discovering what we had forgotten. But there was also the joy of getting to know our partner from Shantou University, Angel. For lunch, we set out to sample the local delicacies—and found ourselves at McDonald’s instead. Over burgers and fries, Angel asked me what Americans thought of journalism. I replied that there was a lot of idealism—journalists guarding democracy and whatnot—but that there was also a lot of cynicism.

After my little diatribe, I returned the question to Angel. What do Chinese people think of journalists? Her answer was much more optimistic. In recent years, journalists had done much to elevate the voices of the unheard, to uncover problems and promote solutions. But, she added, the Chinese people feared the influence of government on the media.

After my little diatribe, I returned the question to Angel. What do Chinese people think of journalists? Her answer was much more optimistic. In recent years, journalists had done much to elevate the voices of the unheard, to uncover problems and promote solutions. But, she added, the Chinese people feared the influence of government on the media.

The night ended in a dark alleyway, not too far from the Forbidden City, with plates of boiled dumplings and rice. When I first met Carlos a year and a half ago at journalism school, he did his utmost to avoid the scourge of chopsticks. Not an easy feat in a city like Vancouver, where the largest visible ethnic minority is Chinese. And there came a day in semesters past when Carlos had to face those two intimidating wooden sticks. I was there to witness the bloodbath. He held the chopsticks like knitting needles, using them to scoop noodles from soup, but more often than not, the noodles splashed back down. Tonight, Carlos had his rematch. There were only chopsticks, no forks. But this time, there was success. And a full stomach.

Shanghai, December 5 2013

David Rummel

Our intrepid Shanghai crew on the food safety beat sets out for a day’s work.

Ironically the air quality index in Shanghai is much worse than Beijing today. The iPhone app says “protection recommended very unhealthy” PM 2.5 level the size of particulate matter that lodges in your lungs is 191–very high.

Shanghai, December 5 2013

Katelyn Verstraten

I will never, ever take clean air for granted again. It’s literally apocalyptic! Crazy to think this could ever happen to Vancouver. It burns my eyes.

Still, we are having a great time in China.

Shanghai, December 4 2013

Jimmy Thomson

Packing for China is an odd experience. I needed some hip clothes for Shanghai, waterproof shoes for farms outside Chengdu, particulate masks for Beijing, and Clif Bars. Lots of Clif bars. I felt like a toddler running away from home, packing three dozen snack bars. It all fit, though, and I met up with Katelyn and Aurora for our flight at 8 a.m. With a fairly uneventful flight behind us, aside from being mistaken for a) a newlywed couple and b) a guy traveling with his two girlfriends (?), we arrived in Shanghai’s Pudong Airport. In retrospect, I’m not sure what I was expecting, but it probably wasn’t an immaculate Starbucks playing “All I want for Christmas is you.”

Packing for China is an odd experience. I needed some hip clothes for Shanghai, waterproof shoes for farms outside Chengdu, particulate masks for Beijing, and Clif Bars. Lots of Clif bars. I felt like a toddler running away from home, packing three dozen snack bars. It all fit, though, and I met up with Katelyn and Aurora for our flight at 8 a.m. With a fairly uneventful flight behind us, aside from being mistaken for a) a newlywed couple and b) a guy traveling with his two girlfriends (?), we arrived in Shanghai’s Pudong Airport. In retrospect, I’m not sure what I was expecting, but it probably wasn’t an immaculate Starbucks playing “All I want for Christmas is you.”

Shanghai, December 4 2013

Katelyn Verstraten

An hour after we arrived in Shanghai, my IRP teammates and I went for an evening walk to stretch our legs. We walked past a crowd of middle-aged Chinese dancing to music (called dama) and stores selling entire plucked dried chickens, chatting.

“How do you find the air quality in Shanghai so far?” asked Cherry, our Chinese student partner from Shantou University.

I paused and inhaled deeply. The air felt thicker than Vancouver’s ocean perpetual breeze, but I could still breath.

“It’s fine!” I replied as an optimistic jogger ran by wearing a smog mask.

Cherry started laughing. “Right now the air quality is one of the worst in China!”

Oh.

Shanghai, December 4 2013

Aurora Tejeida

Today one of our interviewees took us to a typical Shanghai crepe stand. It was a woman selling crepes out of her apartment through an open window. It was interesting that even though the woman we had just interviewed is very concerned about food safety, she believes that crepes are safe because they are not boiled in oil (if you want to know what I’m talking about Google ‘gutter oil China’).

I don’t know if the crepes were safe, but they were definitely delicious. Immediately afterwards, we went to a nearby mall where we got pork dumplings. One important tip about eating them is to always poke a hole in them first to let all the liquid out before putting it in your mouth.

Another tip I wish I had known is to poke several holes in the dumpling and turn it upside down. They probably taste even better when you don’t burn half of your face while trying to eat them, but it was worth it.

I’m looking forward to trying more interesting dishes.